New Book Explodes Myth about Cost of Instruments Used By Sir C V Raman

- News

- 2.9K

It is a part of folklore about Indian science that Sir C V Raman made his Nobel-prize winning discovery in 1928 using instruments which cost just a few hundred rupees. A new book by a science historian has busted this myth.

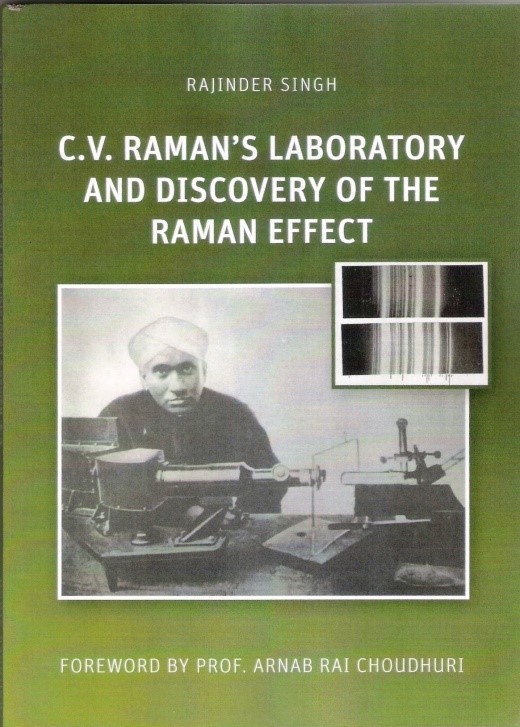

Dr. Rajinder Singh, a well-known historian of science, in his new book titled C.V. Raman’s Laboratory and Discovery of the Raman Effect, has brought to light certain hidden aspects of the Nobel laureate’s life and work. This is Singh’s third book on Raman.

The book provides a full account of how Raman and his students created and perpetuated the myth that Raman Effect was discovered by spending just 200 to 500 Indian Rupees. The myth was floated and publicized in national newspapers (The Bharat Joyti, National Herald, Indian News Chronicle) in the 1940s and in the memoirs written by Raman’s students. It was projected that the facilities available at the Indian Association for Cultivation of Science (IACS), Calcutta, where Raman did his experimental work, were poor.

In newspaper interviews, Raman himself spoke about poor facilities available for Indian scientists. The cost of equipment used by Raman, as mentioned in newspaper articles, ranged between Rs 200 and Rs 500. Raman’s biographer and one of his former students, A. Jayaraman, wrote that “the equipment which Raman employed for the discovery was very simple and amounted to a total cost of 500 Rupees at the time.”

The new book provides a detailed list of instruments used by Raman with their cost. Their total cost has been worked out to be Rupees 7630, excluding money spent on chemicals, which cost a handsome amount those days. It details the circumstances and instruments used during discovery of Raman Effect step by step on the basis of the diary of his co-scientist K S Krishnan from February 16, 1928, onwards. The chapter is a compendium of instruments such as mercury lamps, light filters, spectroscopes and other accessories required for Raman’s investigations leading to his discovery and the Nobel Prize.

Raman started his research activity in 1907 at IACS and it included areas as diverse as acoustics, optics, X-rays, and crystallography. His research team included the best talent available in India, as shown in the book. The library of IACS subscribed to 100 popular scientific journals from Europe. Thus the research facilities were not only adequate but almost ‘unlimited’, according to the author. It was Raman’s dream to make IACS an international center of research in India.

“Raman had a huge team of 36 trained researchers; well-equipped laboratories and workshops, and his own journal. Thus under these circumstances, it is wrong to tell that Raman worked under ‘poor’ conditions,” the book has pointed out.

In the chapter titled “Instruments for the Discovery of Raman Effect”, Singh laments that “as far as India is concerned, the history of scientific instruments is relatively unknown. Even the instruments ‘made’ or bought by renowned physicists like C V Raman, M N Saha, and S N Bose have not been properly preserved”.

The book points out that Raman was in the habit of complaining about poor conditions, especially after his visits to European laboratories. In a letter written to the Registrar of Calcutta University, he boasted: “From the experience I have gained in travelling in different parts of the world and visiting the great centres where experimental research in physics is carried on, I can assert without hesitation that the facilities available to the Palit Professor of Physics for the carrying on his duties at the College of Science are miserable in the extreme.”

Besides the instruments used by Raman, the book provides an account of Raman’s general activities as a faculty member, his opponents at the University of Calcutta and the international honors received by him as Palit Professor.

Asutosh Mookerjee, an educationist, and judge who later became Vice-Chancellor of Calcutta University was a staunch supporter of the scientist. Raman was made Palit Professor of Physics even when he had no foreign research degree equivalent to D.Sc and that too on his own terms and conditions against the rules of the University. However, Raman proved his worth by winning a Nobel Prize in 1930.

Raman was provided “Ghose Travelling Fellowship” under which he could visit most of the research laboratories in Europe, USA, and Canada. He wrote a proposal for expanding his research activities after such visits which were rejected by the university. He wanted to change rules for Ph.D. registration but the University Senate did not approve the idea. Raman fully participated in university administration and accepted assignments in various academic bodies of the university. He preferred Bengali as the medium of instruction over Sanskrit.

The most interesting section in the book talks about Raman’s so-called opponents at the university. In one instance, Raman annoyed J C Bose by offering a higher salary to his trustworthy mechanic to uproot him from the Bose Institute. Raman was highly critical of research work of J C Bose and did not spare a moment to criticise him even after his death. The other scientists of the Calcutta School who did not see eye to eye with Raman were M N Saha, B S Guha, U N Brahmachari and Ganesh Prasad. The author has revealed his acumen to bring to light the reasons for the conflict between the dons of Calcutta University and Raman.

Ultimately, all opposition to Raman fizzled out after he got international honors as Palit Professor. He was conferred the Fellowship of Royal Society London, Knighthood of British Empire, and the highest award in Physics, the Nobel Prize. I want to finish my review with brilliant but somewhat sarcastic remarks of Arnab Ray Choudhury: “Raman as a scientist possessed many extraordinary qualities – the brilliance of mind, astute intuition, dogged determination, tenacity, an almost unbelievable capacity for hard work – certainly modesty was not one of his qualities”. (India Science Wire)

About the book

Author: Rajinder Singh, University of Oldenburg, Germany

Publisher: Shaker Verlag GmbH, Aachen, Germany

Year of Publication: 2018; Price: 21.90 Euro; Pages: xvi + 153.

By Dr. Hardev Singh Virk

For the latest Science, Tech news and conversations, follow Research Stash on Twitter, Facebook, and subscribe to our YouTube channel