Women Who Contributed To Shaping Science And Medicine In India

- News

- 2K

Much has been written on the life and work of renowned scientists like C.V. Raman, Meghnad Saha, S.N. Bose, and Homi Jehangir Bhabha, but the contribution of women scientists is almost ignored. In recent decades, a few books have been published to address this void.

At the beginning of the 1990s, Dr. Sharayu Bhatia, herself a pioneering medical professional, wrote a monograph titled “The First – Life sketches of medical women in India” with a foreword by another pioneer Dr. Sushila Nayar. The book had featured 27 Indian and western women in the field of medicine who had lived in the 19th and 20th centuries such as the first missionary in India to initiate medical relief, the first Indian to study medicine, and the first women to receive government scholarship for study in England. Another important compendium on women scientists – Lilavati’s daughter: Women scientists of India, was published by the Indian Academy of Sciences, Bangalore in 2008.

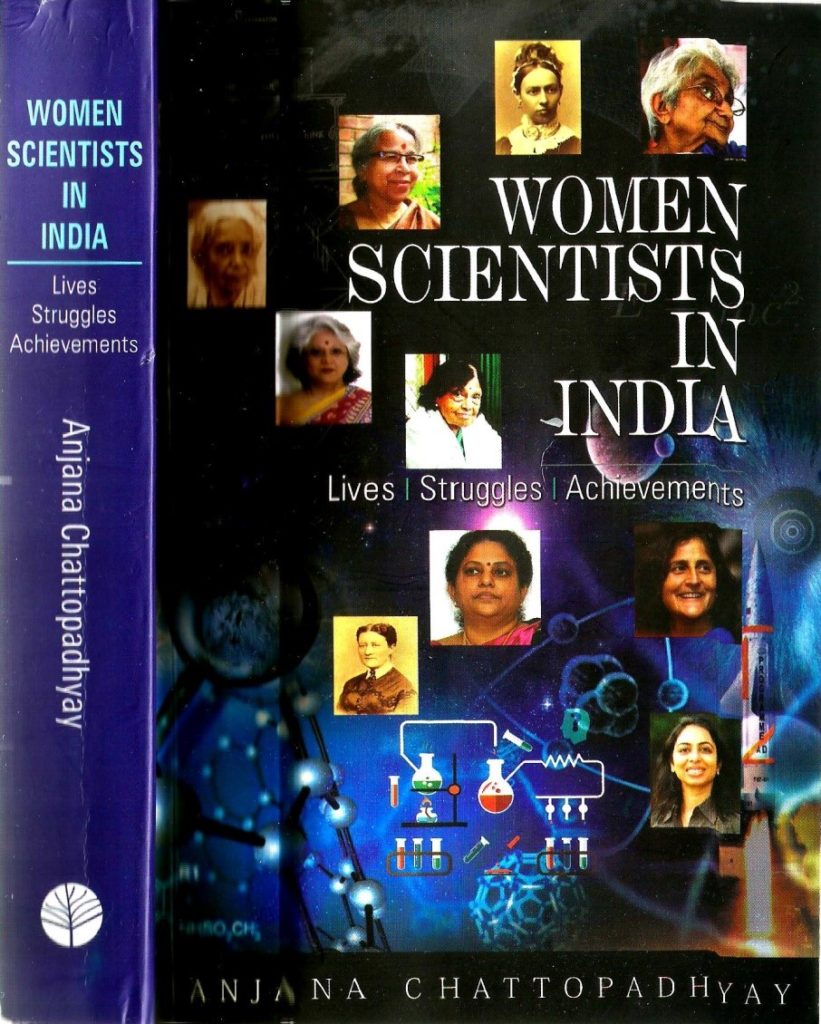

Now a new book by Dr. Anjana Chattopadhyay details life sketches of 175 women scientists – Indians or foreigners who were either born or had worked in India. Dr. Chattopadhyay is known to the historians of science for her monumental books, “Encyclopaedia of Indian Scientists” (1995) and “Dictionary of Indian Scientists” (2002). Her new book “Women scientists in India: Lives, Struggles & Achievements” includes 14 entries from the first book and 40 from the second book. In the new book, short biographies are better illustrated than in the previous books.

The women featured in the book were included based on certain criteria such as reception of national and international awards; contribution to specialised or super-specialised subjects; establishment of departments and institutions in the field of science; ‘scientists, who made new theories, discoveries and innovations, implementation of which made visible impact upon the society.’ The majority of the listed scientists belong to medicine and related fields, while some are from the fields of astronomy, botany, chemistry, mathematics, and physics. The book also provides important data such as a list of women Padma awardees in Medicine from 1954-1999 and a full list of Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar awardees from 1958 to date.

It interesting to see why women took to work in medicine and health in earlier times. It emerges that it was due to cultural and religious reasons (such as wearing ‘Burka’) and other personal reasons that some of the women decided to study medicine. For instance, fourteen years old, Anandibai Joshi of Bombay lost her child at the time of delivery, as medical facilities were not available. In order to help other women, she decided to study medicine.

Even in the 21st century, people in the West believe that women are suppressed in other parts of the world, whereas in their own countries they have freedom in all spheres of life. About two to three centuries ago, Christian missionaries and the colonial powers tried to introduce their education system to ‘civilize’ other nations. The book gives different examples, which demonstrate that not only within India but also in western countries, highly educated women did not get proper recognition. For instance, the Royal Society of London (founded in 1663) elected women Fellows for the first time only in 1944. The Paris Academy of Sciences (founded 1666) did so in 1979 by electing Y. Choquet-Bruhat as Full Member.

In India, the National Academy of Sciences, Indian Academy of Science and National Institute of Science of India (renamed as Indian National Science Academy) were established in 1930, 1934 and 1935 respectively. The last two academies elected E.K. J. Ammal in 1935 and 1957 respectively as the first woman fellow. Dr. Manju Sharma was elected as the President of the NASI for the year 1995-1996. At the beginning of 2020, Dr. Chandrima Shaha is going to be the first woman President of INSA. The present book gives short biographies of Sharma and Shaha.

The book is a treasure of knowledge from a historical point of view. However, its title is misleading because neither a doctor nor an administrator nor founder of an institution could be called a ‘scientist‘ unless he or she has done research work. From this point of view, some of the women included in the book cant be called a scientist. For example, Clara A. Swain, who was the first medical missionary to provide medical relief.

In many instances, the author has not discussed the ‘struggle’ part of women scientists. Still, the book has successfully highlighted the contribution of women to social, political and scientific life in India. It is recommended for general readers, students, historians of science and technology, and feminism studies. (ISW)

If you liked this article, then please subscribe to our YouTube Channel for the latest Science & Tech news. You can also find us on Twitter & Facebook.